Telecoms: Our story so far

by SF Team, 26 September 2017

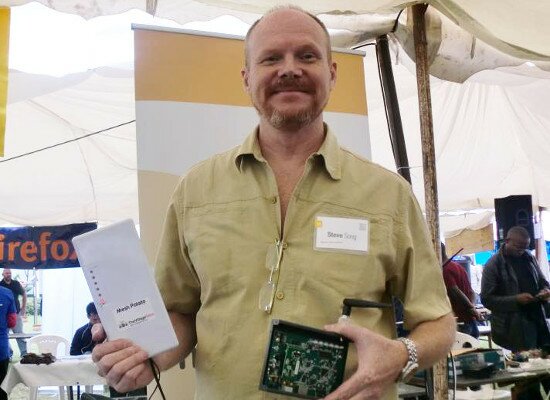

https://www.flickr.com/photos/ssong/5181722490

Telecommunications was one of the first areas we invested in. We recognised that being able to connect to other people and ideas was fundamental to being part of the emerging digital citizenry. Just being in touch could unlock innovation we could not yet imagine.

Having spent many years working in ICT for Development in Africa, Steve Song joined the Foundation in 2008 as one of the first Fellows. He articulated the missed opportunities for users and regulators alike resulting from overpriced data access in emerging economies and made a number of regulatory policy recommendations based on his experience and research, along with mapping the progress in undersea cables around Africa. In the absence of a telecommunications industry with a development agenda, Steve worked with the open source software and open hardware communities to find a solution that could be implemented and operated independently, at low cost. They decided on using mesh networking, establishing Village Telco. The idea was built upon the finding the majority of mobile phone calls in South Africa at the time were between phones within the same cell tower range, i.e. very local. This means people could establish their own, independent networks to speak to those closest to them - family, friends, their local school or clinic. They no longer had to walk to speak to someone, especially after dark or in an emergency.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/macjordangh/4933989491

Village Telco succeeded in proving that local communication was valuable and important, and that cost was a significant inhibitor of communications. Village Telco was only possible because they could use wifi, an unlicensed band of spectrum, which was open for anyone to use and experiment in. This was in part also why this solution did not scale. Users had to purchase specific equipment to be able to join, and relied on a network of their neighbours to keep them connected.

Paul Gardner-Stephen recognised the opportunity mesh networking offered, but also knew that people wanted to be mobile. By 2011, when he joined the fellowship, many more people owned mobile phone handsets. He applied the Village Telco approach to mobile instead of fixed line telephones and so established The Serval Project. Where Village Telco focused on urban areas where cost was a significant driver, Serval was most interested in providing a solution to communities where there was no mobile phone coverage at all, either because of their remote location or as result of a natural disaster. He was inspired by his own experiences in rural Australia and the total collapse of communication infrastructure during the Haiti earthquake of 2010.

http://smaflinders.blogspot.co.za/2012/06/

A clear benefit of the Serval approach would be that people could use the mobile phones they already owned. They could be on the move and would not be reliant on or limited by a pre-installed base station. Unfortunately the mobile nature also meant that it was difficult to maintain a stable connection. Users also had to root their Android device and install Serval firmware to participate effectively. This undermined the benefit of using a device you already owned.

Both Village Telco and Serval offered solutions that were independent and free to use, operating completely outside of the regulated telecommunications space. While there were many potential benefits around this, the inability to scale or interface with mainstream communication networks at the time, meant that they failed to become viable solutions. What they did do, was make a valuable contribution to the future of ubiquitous, affordable telecommunications by setting that vision so clearly and deliberately making building blocks available freely and openly.

While supporting his wife’s work in community radio, Peter Bloom drove up and down mountain passes visiting remote villages in Oaxaca, Mexico. He was stunned by the complete lack of mobile network access there. It was simply not worth their while for established mobile phone operators to invest in infrastructure in these areas. With only 2-3 phone landlines reaching each village, it meant that contact with the outside world was limited to what this small bottleneck would let through, with no privacy and high likelihood that connections would be missed altogether. Peter found this not only inconvenient, but fundamentally unjust, and he set out to find a solution.

As he explored possible localised telecoms solutions, Peter connected with both Steve and Paul. He built his first installation of a community owned and operated network on the work they had done and shared, and the lessons they learned from testing and failing. In 2014 he joined the Shuttleworth Fellowship, through which he adapted and expanded the Rhizomatica model, focusing on making integration seamless for users and ensuring that they could legally and sustainably use mobile phone spectrum.

http://wiki.rhizomatica.org/index.php/File:Telefono-usuario.JPG

As with Steve Song’s Village Telco and Paul Gardner-Stephen’s Serval Project before, Peter Bloom made sure that Rhizomatica’s vision, methodology and necessary tools were shared back into the open source software and open hardware communities. Not all of the equipment Rhizomatica uses is open, but all of it is readily accessible at reasonable prices and can be acquired by anyone without restriction. Rhizomatica is also very clear about what they use, and how, to allow anyone else to replicate their approach, as is being done in 4 countries.

But the technology implementation is not the most world changing part of what Peter did. The Rhizomatica team put ubiquitous telecoms access on the agenda of the Mexican government and as a result negotiated the first ever community mobile phone network operator licence. This not only changed the telecoms landscape in Mexico, but is being considered for adoption at the ITU and in selected other countries in Latin America and Africa.

Village Telco, The Serval Project and Rhizomatica focused on underserved communities, but there are also gaps in overserved communities. Urban areas are becoming more congested with wifi signals almost daily and urban density makes installing cables bothersome, slow and expensive. Internet users within close range of backhaul connections miss out on its maximum capacity.

Luka Mustafa saw an opportunity to apply his academic research to this real world challenge. He joined the fellowship in 2015 to work on Koruza, which delivers wireless communication through free-space optical network systems. Koruza makes building-to-building high speed data transfer possible using an infra red light beam. This technology existed before, but was closed within a proprietary application, primarily serving the military, unaffordable and generally unavailable to civilian users.

http://irnas.eu/

Like the approaches of telecoms fellows before him, Luka’s work enables organic growth of networks, putting users in control of their own connectivity where systems have failed to deliver. The designs of his system are available freely and openly to anyone to build, adapt, manufacture or sell. He has also taken this approach to designing and delivering engineering solutions to other fields, working with clients and partners to scratch their own itch while sharing value with the larger open hardware community.

What does this journey say about how we fund? We support progress, not just innovation. No single idea will solve the biggest social challenges we face. But no effort will be wasted, no project a failure, as long as the outputs and outcomes are openly shared. Almost a decade after first starting to work in this area, the original vision of ubiquitous, affordable access still holds, and we are getting closer to realising it. That would not be possible without having worked with each of the Fellows we have had, testing the ideas and implementations, and incorporating the experiences of others in the free and open community.

Progress is not linear. We could not have mapped out this exact trajectory when we started 10 years ago. We started with a big vision and found someone we thought could add to it. Apart from investing in their ideas, we also invested in Steve, Paul, Peter and Luka. Having the time and space to experiment helped them expand their own knowledge, shift thinking and develop some of the components they are still using today. As the landscape evolves, they adapt to continue serve our shared vision. This means that our funding has a sustained impact well beyond the scope of what we directly support.