Konstantin Dmitriev: Animating Opportunity With A Flash Grant

by Chris McGivern, 15 May 2021

https://www.synfig.org/category/news/page/5/

Konstantin Dmitriev’s tale of improving open source 2D animation tools with a Shuttleworth Flash Grant award is a heartening example of what we hoped the programme might enable. Speaking at our recent FlashForward event, he describes how the grant spurred him to turn a quiet, extremely isolated town in Russia into an unlikely hub for open source animation and the impact it had on his and others’ lives.

Konstantin is a self-educated animator and open source advocate from Gorno-Altaysk in Siberia, Russia. His home town is nestled in a snug valley enveloped by the north-western Altai mountains and virtually at the centre of Eurasia, at almost the precise midway point between Finland and Japan. It’s a small, beautiful place, but very remote and surrounded by Russia’s most sparsely populated region.

As a child in this quiet town, Konstantin would often shoot homemade movies and create basic animations with his brothers. A love for Japanese anime tipped the balance between the two disciplines as he grew older, along with a dose of realism and a developing DIY ethic. “You need actors, lights, decorations, good weather and a lot of money to make a movie,” he smiles. “And I always wanted to be independent. With animation, everything is in your own hands.”

But there were limited options available for Konstantin to pursue his passions via the traditional routes. College courses were nonexistent in the province, and there was little potential to move elsewhere. He decided to teach himself.

“It was difficult to find animation software around that time,” he explains. “I eventually built up some experience with proprietary software and used it until I discovered Linux and the concept of open source. It completely changed my vision.

“I could see people sharing, communicating and helping each other, and I felt it was for me. So I moved to open source tools, and in 2006, a friend of mine told me he’d found a 2D animation application called Synfig.”

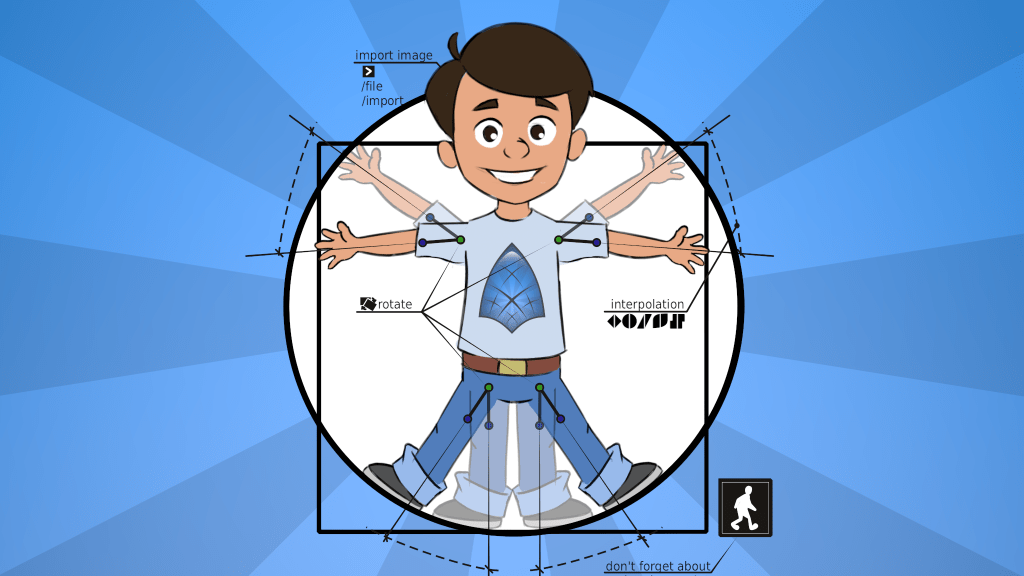

Synfig was initially created by an American called Robert Quattlebaum for his animation company, Voira Studios. It was a powerful tool to eliminate the need for 2D animators to hand draw every frame, thereby dramatically reducing the vast expense of production. But after Quattlebaum realised it would fail on the market, he decided to open source it under a GNU license. In a 2006 interview with OSNews, he said: “Ultimately I’d rather everyone be able to use Synfig than no one, so I decided to go ahead and release it to the world.”

Intrigued by the prospect of getting to grips with the first open source 2D animation tool he ever encountered, Konstantin took a closer look. “There were no instructions,” he recalls. “It was just the application and a few animated demonstrations. A small group of us started digging into its code, trying to understand how it worked. Everyone was scratching their heads. Nobody was a professional coder, and no one was a professional animator; we just had a keen interest.”

This small group of volunteer hobbyists continued working with Synfig in their free time for years, slowly getting to grips with the powerful but unstable software. Minor improvements appeared here and there, and they were learning all the time, but discussions around speeding up development led nowhere.

“Also, the community was growing and would often send ideas for fixes and new features, but none of us had the knowledge, skill or time to do anything other than work on the small ideas. And we all had jobs,” says Konstantin, who was teaching animation to college teenagers at the time.

It was slow progress, but Synfig was far from drifting aimlessly, thanks to a combination of open source spirit and artistic endeavour. Alongside their work on the code, the contributors had started the Morevna Project with an idea to create an animated short using only free and open source 2D animation tools. The project instilled a keen desire to improve Synfig and kept everyone on track. It took five years and a small, global community of committed contributors to finish Marya Morevna as a demo and the first instalment of the Morevna Series. The animated short was ready for premiere in 2012.

By this point, the project had slowly become of interest to Julia Velkova, a PhD student at Södertörn University in Sweden. She was seeking out subjects for her research dissertation on free software for media production and saw something compelling in Morevna and Synfig.

“I worked with Julia for a few years,” says Konstantin. “She was particularly interested in the Morevna Project and did some work with us, helping with translations and giving advice. One day, just as we were planning to release Marya Morevna, she mentioned a big conference in Sweden. We started talking about it, and it gave me an idea.”

The idea was bold and paid off in more ways than one. Firstly, Konstantin persuaded Julia to write a letter to the government and make his invitation to the FSCONS conference official. The government agreed to pay for a three-day trip to Sweden, and the two of them presented a talk about open source animation tools before Konstantin unveiled Morevna’s first-ever animated short. Unbeknownst to Konstantin, the other payoff was sitting in the audience: a future Shuttleworth Fellow.

Jonas Öberg was a well-respected figure and leader in the open source movement and a few months away from starting a Shuttleworth Fellowship when he met Konstantin. They spoke at length about 2D animation, Synfig and Morevna, and the conversation clearly stuck in Jonas’s mind. When his fellowship began in the following spring, Konstantin was his first Flash Grant nominee.

“I didn’t believe it at first,” says Konstantin. “It seemed too simple, and for a moment, I just thought someone was playing games. Even when I saw it was Jonas’s nomination, I thought the transaction wouldn’t go through, or some other variable would get in the way. I didn’t have any experience with grants or awards, and we had never thought about getting money to develop Synfig before.”

That soon changed. Konstantin immediately saw an opportunity to make significant progress with Synfig. He paid a developer for three months, whose work made dramatic improvements that sparked a lot of new interest from the user community. He used the rest of the money to create an educational course, teaching new and old users alike how to get the most out of Synfig.

“The user community was so impressed with the results,” explains Konstantin. “We could see people were enthusiastic, so we crowdfunded with success for the next nine months. And that’s not all. We began getting recurring donations, and not long after we reached a point where we didn’t have to spend time and effort on crowdfunding.

“The training course was also important,” he continues. “It had two impacts. The first is additional funding. We set up the course as ‘pay what you want’ or a minimum of one dollar. But the second impact is more important.

“It allowed us to share knowledge. People could understand the concepts and start using the software quickly. Synfig is not used much by professional animators but the course opened doors to newcomers and hobbyists interested in animation. We have started to hear of many schools and educational establishments using Synfig, not just in Russia but also in other countries.”

Receiving a Flash Grant started a chain of events that meant Konstantin could focus all his time on his dual passion for technology and art. With enough income arriving from donations and course payments, Konstantin quit his day job of teaching, enabling him to run free animation workshops for teenagers, working exclusively with open source tools.

“Our goals were to improve open source software and to help people learn animation and popularise it around the world,” he says. “That means educating people and making animation my life. We are part of the way there.”

This is incredibly important. Think of the animation industry and big business, expensive movies, and a market worth hundreds of billions immediately springs to mind. Konstantin and his fellow volunteers have developed a small but vibrant alternative to the dominant model. He proves that consumers turn into makers if you nurture them in the right environment and culture, and empower them to explore their creativity and passion. There is a legacy piece to this, too: the young people he teaches will help the studio and Morevna Project grow while improving Synfig and drawing new people into the philosophy and practices of the open source community.

It’s important to note that Konstantin’s Flash Grant did not create this change; the potential already existed. Instead, the award sparked a thought, unlocked an idea, and opened the door for a new opportunity.

“I didn’t grow up in bad circumstances or enjoy fewer opportunities than others,” he concludes. “My primary motivation from the beginning was to demonstrate that someone doesn’t need to find a better place, where there are prepared conditions and opportunities available.

“Instead, I want to explore the possibility of transforming the place where you are already and to create the right opportunities and conditions yourself. I grew up in a society where people used to neglect the latter scenario, so I always wanted to create proof that such a possibility could exist.”