A Modest Proposal - The 1 cent SMS

I am filled today, as is often enough the case these days, with a sense of righteous indignation. In a meeting earlier today, Dominic Cull (firebrand lawyer for the forces of telecommunications good in South Africa) pointed out the obvious. He said that one of the single most important things mobile operators could do to make a difference for the poor would be to drop the price of SMS charges. The funny thing about the obvious is that we often don’t see what is staring us in the face.

For those who may not be familiar with the technology of SMS, it doesn’t cost a mobile operator very much to send and receive SMSes. In fact, for GSM networks, SMSes are sent on a signalling channel which means that they don’t actually take up any traffic that would otherwise be used by voice calls. So, with voice infrastructure, mobile operators basically get SMS infrastructure for free. Now, that doesn’t mean that it is free for operators to provide. There are obviously billing and technical systems that need to be maintained to ensure that SMSes continue to function but it is about as close to free money as you can get.

For those who may not be familiar with the technology of SMS, it doesn’t cost a mobile operator very much to send and receive SMSes. In fact, for GSM networks, SMSes are sent on a signalling channel which means that they don’t actually take up any traffic that would otherwise be used by voice calls. So, with voice infrastructure, mobile operators basically get SMS infrastructure for free. Now, that doesn’t mean that it is free for operators to provide. There are obviously billing and technical systems that need to be maintained to ensure that SMSes continue to function but it is about as close to free money as you can get.

About a year ago there was a blog post on the high cost SMS, subsequently picked up by Slashdot, which raised a small storm of indignation about the cost of SMS. In December last year, New York Times published an article highlighting the failure of the chair of the Senate anti-trust subcommittee to get anything like a reasonable explanation from operators on why SMS charges in the U.S. had doubled between 2005 and 2008 in the United States.

So what are the facts? The global average cost of an SMS is about 10 U.S. cents per message. Here in South Africa the cost of an SMS is R 0.75 or about 7 U.S. cents per message. Doesn’t sound like very much until you consider that, according to the ITU in 2006, the global SMS market is worth about 80 billion U.S. dollars annually. The New York Times article estimated that 2.5 trillion SMS messages were sent globally last year. A Huawei article estimates that 80-90% of SMS revenue is profit.

How is this possible? Why haven’t market forces brought the cost of an SMS down to something somewhat related to its cost + a reasonable profit? Why are consumers paying ten times the cost per SMS? Communication technology has gotten more sophisticated, less expensive, more automated and SMS volumes have sky-rocketed, yet on average cost per SMS has gone up. So what is up with that? A communications regulator doesn’t have to look much further for evidence of market failure.

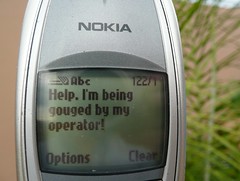

So why do people put up with this? Partly, I think it is because behaviour in spending on mobiles is not entirely rational. Having anchored high prices for SMSes, it is comparatively easy for mobile operators to simply carry on charging high prices. Everyone, rich or poor, needs access to communication. For the poor, as expensive (comparative to cost) as SMSes are, they are still the cheapest form of pervasive electronic communication. Consider this in a context where poor Africans are spending over 50% of their disposable income on mobile communication (see the table below for more detailed information). What this amounts to is a level of price gouging on the part of mobile operators in developing countries that verges on the criminal. They make the highest profit margin on the service the poor need most.

So here is my proposal. The 1 cent SMS. Let’s challenge mobile operators to make a real difference to the poor by dropping pay-as-you-go SMS charges to 1 U.S. cent per message. Applied globally that would reduce SMS revenue to 8 billion dollars; arguably still a tidy sum. However, that is not taking into account the upside for operators. The reduced SMS costs would enable increased SMS traffic and new, as yet unthought of SMS-based enterprises such as Nathan Eagle’s innovative txteagle start-up.

To get a more complete sense of what people are paying for mobile communications in Africa, here is an excerpt from Alison Gillwald and Christoph Stork’s 2008 publication “Towards Evidence-Based Policy: ICT Access and Usage in Africa“, published by Research ICT Africa,

Monthly expenditure for mobile telephony as share of income and disposable income

| Monthly mobile expenditure / monthly individual income | Monthly mobile expenditure in / monthly disposable income | |||||

| All | Bottom 75% in terms of individual Income | Top 25% in terms of individual income | All | Bottom 75% in terms of disposable Income | Top 25% in terms of disposable income | |

|

Benin

|

11.7%

|

18.0%

|

7.9%

|

32.9%

|

39.8%

|

28.0%

|

|

Botswana

|

10.4%

|

14.9%

|

6.1%

|

43.2%

|

50.4%

|

30.6%

|

|

Burkina Faso

|

14.1%

|

19.3%

|

7.6%

|

32.3%

|

42.1%

|

22.6%

|

|

Cameroon

|

10.8%

|

16.0%

|

4.8%

|

40.9%

|

47.0%

|

32.8%

|

|

Côte D’Ivoire

|

10.1%

|

14.1%

|

4.9%

|

39.6%

|

47.2%

|

31.3%

|

|

Ethiopia

|

7.1%

|

23.3%

|

6.1%

|

37.0%

|

67.1%

|

35.7%

|

|

Ghana

|

13.0%

|

16.0%

|

7.1%

|

47.9%

|

55.3%

|

34.3%

|

|

Kenya

|

16.7%

|

26.6%

|

7.8%

|

52.5%

|

63.6%

|

39.9%

|

|

Mozambique

|

11.7%

|

17.9%

|

9.2%

|

32.6%

|

50.8%

|

18.3%

|

|

Namibia

|

9.2%

|

13.1%

|

5.7%

|

25.3%

|

32.9%

|

17.8%

|

|

Nigeria

|

13.7%

|

17.0%

|

8.2%

|

52.4%

|

60.9%

|

28.9%

|

|

Rwanda

|

10.3%

|

16.9%

|

8.5%

|

65.5%

|

64.9%

|

65.6%

|

|

Senegal

|

14.2%

|

19.4%

|

9.6%

|

22.2%

|

30.1%

|

13.7%

|

|

South Africa

|

7.4%

|

10.9%

|

4.8%

|

29.3%

|

38.2%

|

16.7%

|

|

Tanzania

|

15.4%

|

22.1%

|

11.5%

|

28.9%

|

40.6%

|

20.5%

|

|

Uganda

|

10.8%

|

18.0%

|

7.4%

|

48.6%

|

68.9%

|

39.0%

|

|

Zambia*

|

10.8%

|

14.4%

|

8.6%

|

60.3%

|

73.9%

|

44.1%

|

* Results for Zambia and Nigeria are extrapolations to national level but not nationally representative.

Related posts:

- The Rationality of Mobile Spending Richard Heeks has written an interesting post entitled Mobiles for...

- South Africa: Income Spent on Communication The conventional wisdom in the ICT4D community is that people...